What does a Pharmacy Benefit Manager do?

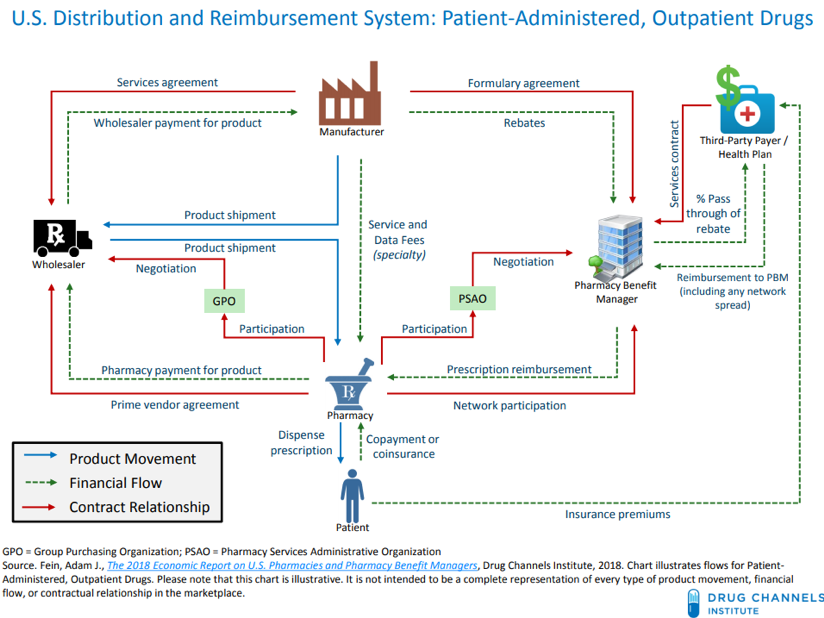

A Pharmacy Benefit Manager (PBM) is a firm that is hired by health plans, HMOs, and self-insured employers to negotiate pharmaceutical pricing arrangements between drug manufacturers and the PBM’s network of pharmacies. They fit into a complex supply chain that prescription drugs follow to get to the consumer, which is best illustrated by this graphic from the Drug Channels Institute:

PBMs manage a multifaceted set of obligations to the different parties they interact with. For their clients, the health plans, they must work out deals with manufacturers to get lower drug prices. For the manufacturers to lower their prices, the PBMs promise them a better spot on the “formulary,” or list of preferred drugs that are offered to the health plan’s patients. (In reality, each PBM has multiple formularies, as each client can help to shape its own formulary structure. Formularies are also partially determined by non-financial factors such as clinical effectiveness of drugs compared to competition.) Better positioning on the formulary ensures that more of the drug will be sold, so manufacturers are willing to lower their prices in exchange, usually in the form of a rebate. Finally, the PBM must manage its relationships with the pharmacies in its “network.” This means making sure the pharmacy receives adequate payment for the drugs it dispenses, either in the form of a reimbursement from the health plan or a copay from the patient.

How are they being regulated?

The hot topic in PBM regulation has been the use of “gag clauses” in their dealings with pharmacies. Because the PBM develops drug pricing formulas for the health plans which are separate from the “retail prices” of the drugs, cases can arise where patients would actually pay less for a drug out-of-pocket than they would for an insurance copay—in other words, the drug becomes more expensive for the consumer with insurance than without. In such cases, common sense would dictate that the patient simply shouldn’t use insurance when paying for the drugs; however, the consumer can be unaware of the price discrepancy. When a pharmacy signs a PBM contract with a “gag clause,” the pharmacy is prohibited from informing the patient that he or she would be better off not using insurance. Gag clauses can also prevent pharmacies from disclosing to patients when lower-priced alternatives are available, such as a therapeutically similar generic drug that isn’t on the PBM’s formulary.

Congress passed two laws with near-unanimous bipartisan support that banned the use of gag clauses in PBM-pharmacy contracts.

The first, Know the Lowest Price Act, bans the clauses in Medicare plans, while the second, Patient Right to Know Drug Prices Act, bans them in commercial insurance. The Know the Lowest Price Act takes effect in 2020, while the Patient Right to Know Act is effective now.

What does it mean for consumers?

The outcome, at least for now, is unclear. While many believe the Acts represent a way to create much-needed transparency in the drug pricing system, others question whether this will actually result in any material changes. While the Acts mean pharmacies will be allowed to inform patients of their options without penalty, it does not obligate them to do so. There is also a question of how significant an effect gag clauses have on drug prices in the aggregate, especially since it’s unclear exactly how many pharmacy-PBM contracts actually use them (some PBMs have denied using such clauses).

A 2016 industry survey found that almost 20 percent of pharmacies found themselves “limited by gag clauses” more than 50 times per month, and a Journal of the American Medicine study found that almost one in four prescriptions filled through insurance would have cost less out-of-pocket.

While those numbers may seem damning in terms of frequency, the Journal of the American Medicine also found that those insured by Medicare overpaid for prescriptions by $135 million in 2013—a large number, but a mere 0.03% of the estimated $450 billion spent annually on prescriptions in the U.S. Many point to such statistics as evidence that the Acts may serve as an feather in the campaign caps of sitting legislators, but that further action is needed before Americans begin to see real drug price relief.

Some, too, question whether PBMs are even the proper target for congressional action in the first place. By aggregating the buying power of an entire network of pharmacies, they have a potent bargaining chip when haggling with manufacturers to lower prices. They may be middlemen, but manufacturers would be able to impose more abusive prices on individual pharmacies than they can on a powerful PBM.

The PBM market is concentrated enough to afford its members this buying power—the three largest PBMs (Express Scripts, CVS CareMark and OptumRx) cover more than 180 million people. There is an argument to be made that PBMs do more to lower prices than raise them, and by curtailing the power of PBMs to contractually protect their formularies, they have less to promise manufacturers in exchange for lower prices. On the other hand, a weaker formulary system might break down some of the insulation that formulary-preferred name-brand drugs enjoy from their cheaper generic counterparts, invoking another buzzword in the battle for drug price relief—competition.

Even if increased competition is a potential long-term outcome, it is naïve to assume that the new laws will take effect in a vacuum. The Congressional Budget Office actually estimates that the specific section of the Know the Lowest Price Act which bans gag clauses will cost the federal government $69 million, as PBMs will raise their fees to offset the lost revenue from the clauses. However, other sections of the Act that increase reporting requirements for biologic drug makers will save the government enough money to make up for this reaction.

Whether or not they are a difference-maker overnight, the Acts may be a forerunner of more sweeping legislation to come. They could signal a newfound willingness in Congress to bring more serious drug-price legislation to the table in the not-too-distant future.